Nyimii Kwatl

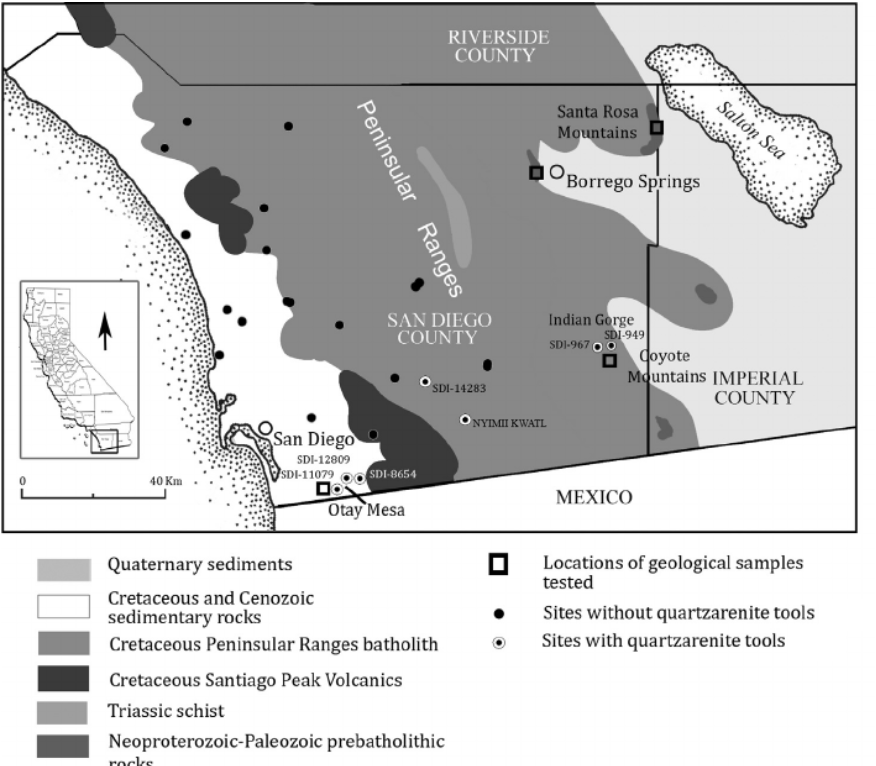

"Terrace of the Sun" - Kumeyaay TranslationNyimii Kwatl, or "Terrace of the Sun", is located in the rugged wilderness of East County San Diego. It sits within the Peninsular Ranges Batholith, a geologically significant area formed during the Mesozoic era over 100 million years agos where other stone enclosure sites have been recognized.

"Enclosures formed by stacked rock walls have been reported from many prehistoric sites in San Diego County, particularly in the Peninsular Range. The ethnohistoric and ethnographic records concerning such features and the archaeological evidence have been discussed by Ronald V. May (1975b, 1975c), Rick Minor (1975b), Joan Oxendine (1981), Richard L. Carrico (1988), and Susan M. Hector (2004)."

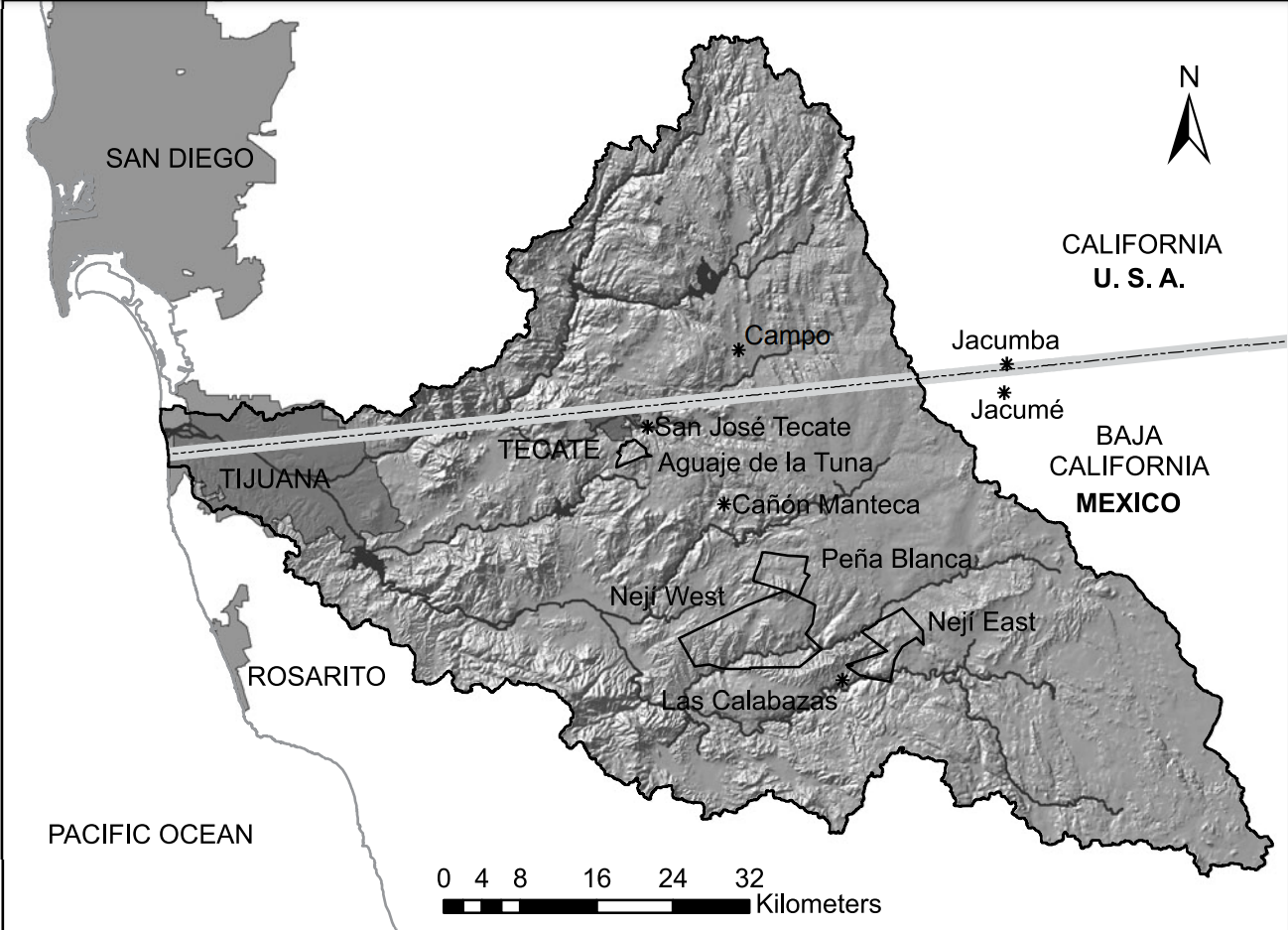

"The cultural landscape of the Kumeyaay living in the Tijuana River Watershed of Baja California embodies the sacred, symbolic, economic, and mythological views of a people who have lived in the region for centuries. Recent research on this region that integrates ethnographic, ethnohistorical, and (to a lesser degree) archaeological information reveals a landscape that is alive and imbued with power, sustenance, and legend - a dynamic construct that reflects both changing Kumeyaay relationships with the land and the group's continuity with the past. Sacred sites, peaks, transformed rocks, magic boulders, and other geographic features associated with oral traditions populate the landscape. Lynn Gamble, Michael Wilken (2008)"

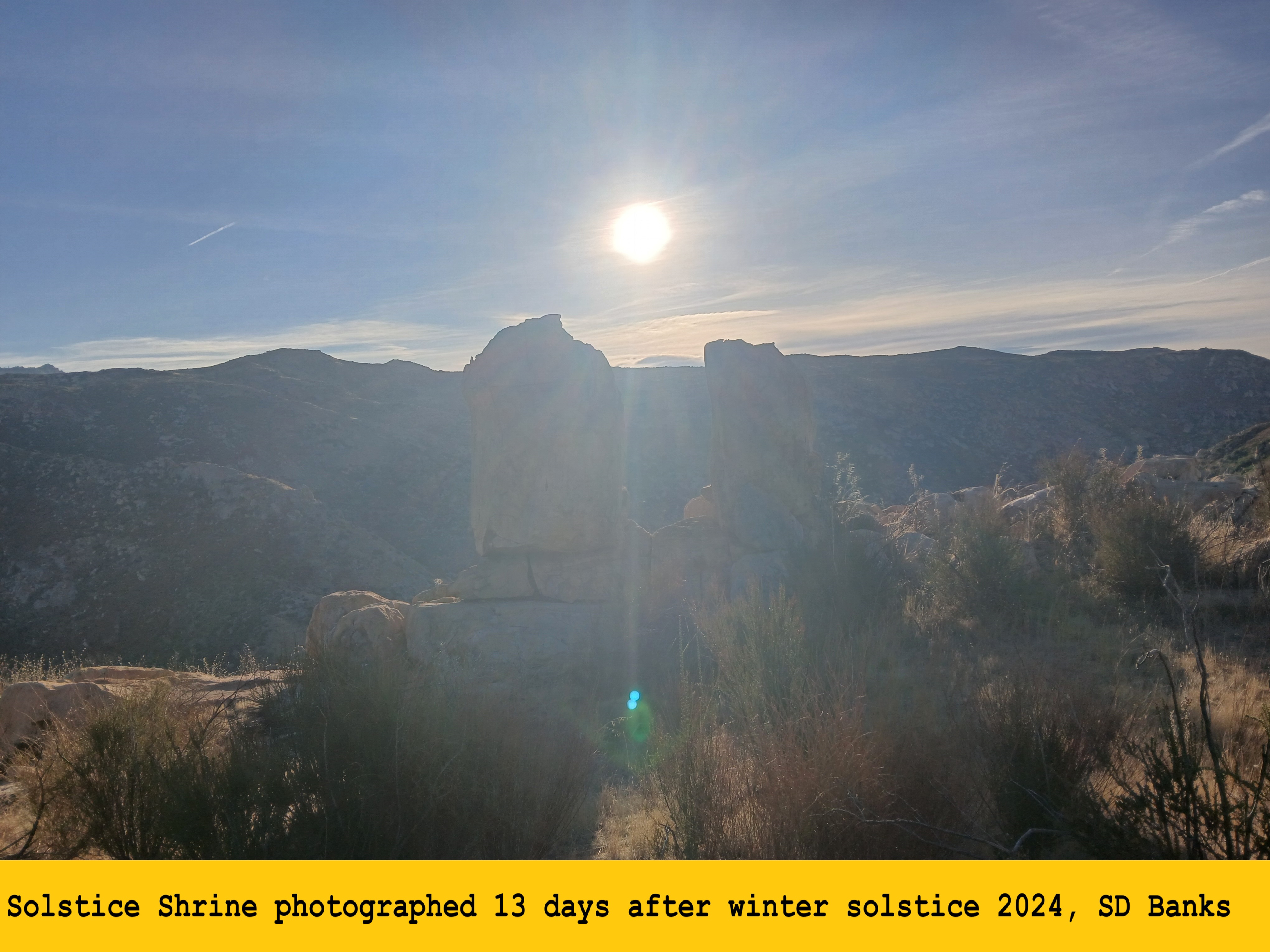

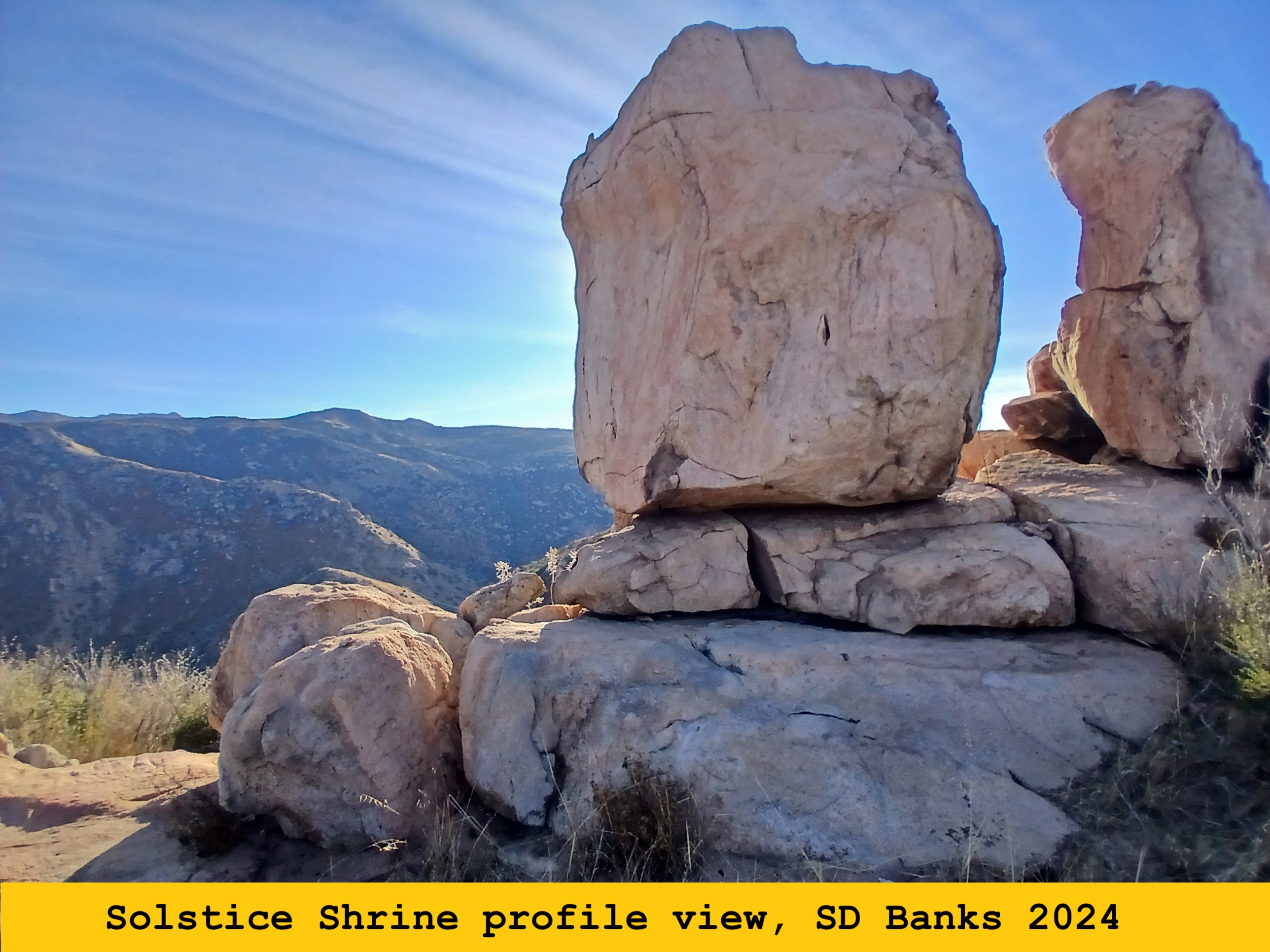

Among the site's most remarkable features is a solstice shrine - on an open terrace over 600 feet above Pine Valley Creek sit two carefully aligned large boulders perched upon slabs on stone. On the winter solstice, the sun rises perfectly centered within this gap, marking an event that likely held profound significance to the original inhabitants of the region. Nearby sits a large bowl ground into a boulder with a blackened base.

This site perfectly echoes the descprition of a similar undiscolsed site in Mexico on the west edges of Nejí West described by Gamble and Wilken (2008). Using the oral historical context from Aurora Meza regarding Spirit of the Mountain we gain invaluable insights on how Nyimii Kwatl was likely used by northern Nejí Kumeyaay:

One symbolically significant place in the region that the Nejí Kumeyaay recognize as a sacred ceremonial site is called the Spirit of the Mountain. It is associated with New Year rituals at the winter solstice. Although the exact site location can not be disclosed here, it is situated on a unique rock formation on the side of a mountain with a dramatic view of the Nejí landscape and beyond. Aurora Meza told us about the annual ritual to the Spirit of the Mountain:

"The tradition is that a fire must be lit on top of the rock. My grandfather used to come. But when he could no longer do it, he put us in charge. We would come every year to put the burning coals up on top. They say that it will bring us a good life, all year. They say that the fire must always be lit, when the New Year arrives it must already be lit; and it looks like this year it's my turn. I hope I'm up for it. I tell my kids that I'll go up on a motorcycle and they can go up on foot! In our language it's called the Spirit of the Mountain. I think it was manmade. They bring here their first hunted catch, their first arrow, or their first song; they can also bring that. It's an altar. They say that the whole tribe would come and wait for the New Year. Someone would go up to light the fire, and the people would be sitting down here on all the rocks you see around to wait for the New Year. Who knows how they even knew that it was a New Year; they didn't even have a calendar. There are times when it's raining. But it's not a problem, it always lights. They don't have a hard time. We do have to gather firewood; look there's some that my sister gathered. The warriors used to leave many offerings; I think they would leave them here in the past. Whether it was their first hunting catch or their first song, they would offer it to the spirit [Aurora Meza, personal communication 2004]."

Nearby, lay a network of bedrock mortars, cupules, and intricately carved grinding bowls, further attesting to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of those who lived here long before us. These features hint at Nyimii Kwatl's role as a place of ceremony, daily sustenance, and deep connection to the natural world.

"Elders repeatedly informed the non-Kumeyaay present that too many people on the mountain for non-religious purposes would destroy the sacred place. They also stated that taking a plant or rock from the mountain would cause the death of the person taking it. Putting something on or near the peak was also forbidden." Shipek (2003)